What portfolio should you hold if you want a basic exposure to the Australian market as a source of equity risk premium?

The benchmark indices are arbitrary in the sense that a large bank is held at large weight simply because it is big. Had a major buyer come in and taken a strategic chunk, reducing the float available in the bank, free-float adjusted exposures would fall. Nothing changed in the operating environment. The benchmark indices are an indication of aggregate holdings available to public investors who do not take strategic chunks of companies. It will produce returns better than the average of such investors due to the presence of frictions. An odds on strategy to be above the money-weighted average of investors is simply not to try to beat the rest. Add tax considerations to this and, depending on the rate and whether you are a trader/investor, these frictions become very meaningful, although a few percent can seem trivial to many on this site...it isn't over time and considerably raises the bar to argue against a pure index approach. Nonetheless, is there a better starting point?

Risk parity is a concept which was brought into popularity by Ray Dalio of Bridgewater Associates, the world's largest hedge fund manager. The idea has evolved to, kinda sorta, build a portfolio whose main components had equal risk contributions (proportion of overall volatility). This was a set and forget technique which required no further judgment about the future performance other than volatility and correlations. That is, no specific return forecasts are made. Dalio's idea was to apply this to a trust for his family after he had passed away...hence no forward looking judgment on returns, beyond estimation of risk.

By doing this, the portfolio is well balanced in terms of risk contributions. Each stock in the portfolio contributes the same amount to the volatility of the portfolio. Risk parity. This takes into account volatilities and correlations, which have been demonstrated to be much more stable in estimation than for return forecasts for such things.

If all banks are essentially the same, adding another bank to the portfolio will see the exposures redistributed amongst all the banks, not an addition to the overall weight. That seems pretty sensible.

In other words, the risk parity portfolio does the best it can with the stocks available to build a widely diversified portfolio. One whose exposures are as widely spread as possible given risk estimates. The very diversified nature of the portfolio helps to protect against estimation errors. It takes into account things like a bank's performance tends to be rather similar to the environment for discretionary consumer behaviour.

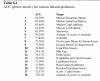

Based on data to late last year, the risk parity portfolio for Australian equities vs the ASX 200 index had the following GICS exposures (I have broken up Financials into finer definitions given their dominance in the Australian market):

View attachment 65719

It has much less exposure to banks, preferring to spread the exposure more towards consumer discretionary stocks and other cyclical sectors (eg. IT and Industrials). The more stable nature of healthcare stocks (in general) sees them being given more weight. Interestingly, the exposure to materials remains fairly in line. I think it is clear that this portfolio is more diverse and possibly a more sensible way to gain exposure to the Australian market components.

The portfolio spreads its exposures differently from simply equally weighting the components. However, the broad exposures do produce a significant bias away from the largest companies. Although the exposure to small capitalisation companies is much larger than for the index, the diversification produced by this portfolio reduces the overall expected volatility relative to the index. By dramatically reducing the exposure to large capitalisation stocks, company specific blow-ups are less impactful and pretty much no company specific event is going to hurt that much.

I believe this concept is a useful consideration in determining a suitable departure point for a portfolio. The expected range of performance of this portfolio relative to the index is +/-2.6% on a 1-std devn basis (ie. within this range two-thirds of the time over a year). This means that variation in physical exposure via the use of index futures is viable. There are also some rebalancing benefits which can be expected. If you think that all stocks in the index are expected to have the same geometric return (if you started them all at $1, they will just wiggle around like dust in the air, which has a small breeze, as the prices evolve. None is particularly destined to shoot away to either extreme), the RP portfolio is expected to produce about 1.4%per annum more from rebalancing effects (it won't get this due to frictions, but an edge will remain).

Unless volatility has some utility as a 'true & thorough' measure of risk is it any better then straight equal weight? Seems like you have to settle the volatility = risk debate before you can really decide if quantitative risk parity is right for you.

I'm all for risk parity within my portfolio but the risk assessment is perception/judgement based- I'm not smart enough to be able to code and quantify risk.