- Joined

- 8 March 2007

- Posts

- 3,064

- Reactions

- 4,296

"Storm at Sea "

It seems appropriate to insert the description of an actual storm we encountered on our 10 year adventure in the open oceans on the ASX decades ago

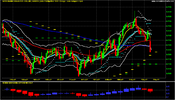

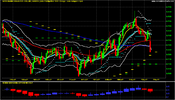

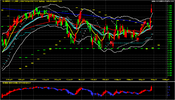

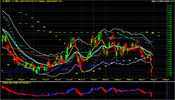

The 3 letter codes may have changed over the ages but the hard lesson of diverging technical indicators should not be lost

This is particularly directed to the novice sea-cadet who for some unexplainable reason believes she’ll be right in the long term if onboard tall ships. It is also relevant to the seasoned veteran who after a magnificent season often forgets the principles of seamanship and lets his adrenalins rule.

Storm is that time all deep-sea yachtsmen must be prepared to face and sometimes without any warning. As we were sailing six tall ships all nearby in the ASX20 it made it possible to analyse the situation more closely afterwards.

The storm took place just south of New Zealand in an area not notorious for extremely fierce gales. However we were quite aware gales there may come suddenly and last for long periods. We weren’t concerned as each ship was toughly built and of heavy displacement. They were the pride of the ASX. Each and every broker in our network with research teams on many floors suggested the big three. BHP, NAB, and NCP and stressed a “diverse and balanced portfolio.”

Julius the only cadet on board asked

“What is the difference?”

Jack replied

“It’s a safety formula so that if any one or two get into trouble the other four will pull us through.” Henry quickly added

“Only if you have equal chips on all.”

We had opted for three industrials and three resources. Jack recommended BPC for its attractive price earning ratio and yield. Benji added WMC because he had fond memories. Henry added MIM as he considered her price a good value bet being the cheapest in the top 20. I abstained from joining the selection table as I saw my responsibility solely as the skipper and navigator.

We had already by now earned an excellent racing record and gained much ground, sailed through many spring gales and came through undamaged.

The NAB was far to the west and by chance the rest of our fleet were bunched together to the east.

On the 20th Dec 93 the chart of the NAB showed a bearish weather pattern and was first hit. There was no hint of a depression forming.

Yet with in 2 weeks the storm was establishing itself amongst the ships.

At midnight the storm caught us.

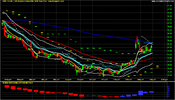

As the barometer plummeted (the white indicator, refer any chart later), violent wind gusts struck the yacht. All the sails were lowered and the boat put in the trough of the sea while we watched for any change. After one day the barometer had checked its fall and the wind’s mean easterly direction was unaltered. The torrential rainfall and screeching gusts all suggested we might be in the path of a revolving storm, or hurricane. The normal instructions for avoiding such storms could no longer be carried out, as the wind was too violent for any canvas to withstand.

The situation as it appeared at 1.00 am. in the middle watch was the very one we had studied most carefully. Not because it seemed likely, but because it was the worst possible position we could imagine for a sailing ship in the open sea.

I assessed that the loss of the tall mast was probable. In this lonely part of the ocean, 500 miles from America and with no engine, survival needed the preservation of all food and water. Nothing could be discarded to lighten the ship. I assessed that crew fatigue would be a danger should a breaking wave smash over the deck or cabin. Finally came the danger of crew being washed overboard. This seemed the greatest hazard of all.

It was clearly best to direct the end of the boat on to the sea to reduce the chance of a wave breaking over her. With such a strong crew I felt a helmsman could always be kept on deck. Even without sails the wind on the bare mast was driving us through the water at near maximum speed.

The night was black. My outlasting impression was noise. The shriek of the wind in the riggings, the din of the waves all blending into one devilish clamour and the pelting rain hammered against one’s head.

Moving around was not easy in these conditions. A novice helmsman could easily be caught off guard while shifting into position. Suddenly, a sea came pounding over the deck, filled the cockpit and slammed against the cabin. The ship was battened down so little water went below. Until one had been on deck for some time it was hard to believe that each succeeding wave would not wash over. If the helmsman could meet each wave squarely with the stern she would rise quietly with the sea and nothing but spray would come aboard.

The problem became chiefly a psychological one. As we were all quite experienced helmsmen by this stage no exceptional difficulty was found in steering the stern into the seas even in the dark. But it was decidedly frightening to hear the furious snarl of a wave breaking astern above the continuous roar of wind, rain, spray and waves hurling themselves at the boat.

I prayed earnestly for the dawn and went down below to look at the barometer. It was still falling steadily. There was a slight easing of the wind but it was still blowing a full gale. As man is a creature of daylight I felt that if we could just survive the night unharmed all will be well. However when dawn should have broken the angry darkness held its own.

Slowly the light seeped through the rain and spray. The dawn was much more frightening than the night. The sight of those huge waves building up astern was devastating. The surface took on a dull dirty and frothy white washing machine character. In the driving spray and rain one could scarcely see beyond the next crest even when on top of a wave.

I had been up all night and the sheer horror of looking at the seas I went below to check all the charts instruments, ate a block of chocolate and write up the log.

If on deck had felt overwhelmingly hostile, the cabin felt like a prison cell. The worst impression was one of utter helplessness. There nothing I could do except trust my instruments.

A spurt of water shot through the tiny peephole left for the helmsman to communicate with those below. I looked out and saw Jack signal me to come up. Conversation was impossible on deck but it was obvious he just wanted some support. He too was frightened by the sight and noise of the seas. Curiously, I found his anxiety reassuring. It did not seem to matter being afraid if a man of his calibre was feeling the same. In any case it felt better to be lending support to another. Strengthened in this way one could think and look around more objectively.

At 5.45 am. on the 25 May, the wind fell dead.

The sudden change was staggering. We had run into a patch of blue sky, colour sparkled, the rain dried up and the spray ceased to drive. On deck our voices were freed. Words no longer vanished in the storm.

“Look at that mountain of sea sir” Jack shouted, forgetting that his voice had not to compete with the elements,

‘It’s breaking in all directions at the top.”

The sea was hopelessly confused. Pinnacles of water would surge up without any form or rhythm. It seemed Mother Nature had developed a taste for modern art. One longed for some wind to steady her but dreaded the return of its overwhelming power. The boats motion was chaotic in the heavy air. Yet Henry and Ben below had somehow wedged and lashed themselves into their bunks. It takes a seaman to rest in such conditions. Every moment they could lie down strengthened our defence.

“I suppose we’re all right, sir,” said Jack doubtfully, “it really scared me to look at those huge curlers astern.”

“Yes, we’re all right,” I replied without much enthusiasm,

“But the real thing is what happens next.”

‘What does happen next, sir?”

‘We seem to be in the eye of a storm, Jack. The strongest wind comes after the calm.”

“I bet no one else has looked into the eye of storm of this size.

“What are we going to do now, sir?”

“Can she stand any more of this ****?”

“She’s stood it so far, Jack. We’ve done all we can. We’re all well trained and ready. There’s nothing left but to pray.” The urge to prey was deep and we were both silent for a minute.

“We’ll pull her through, sir.” warm hearted, loyal Jack said. No finer man could exist to share the pressure. At last there was colour and blue sky, but the mental relief that had come when the wind no longer blew, fizzled out like a spent rocket.

All around swirling, angry, black curtain walls of sea hemmed us in. Seven minutes of a pregnant pause seemed ages.

Savagely the wind pounced again.

It was still from the east. I struggled to check the course from my second compass. (Daily charts explained later) I was surprised to discover they both did not point in a different direction. We were still heading south with the wind astern. I thought of St. Jude and the hope of the hopeless as we sped further from land.

The clock clung to every minute, but at last an hour had passed. The instruments were pumping up and down vigorously as we dived and soared. My obsession with safety was instinctive. My passion for life, insatiable. The hope for some rising indicators never came. At times their fall was checked and then slowly fell again. This was a bitter disappointment. Although I thought the skipper should constantly be on the alert there was nothing I could do about anything and went below to write up the log.

Perhaps the depression is still deepening?

Bon Voyage and Gods' speed

Captain Chaza

It seems appropriate to insert the description of an actual storm we encountered on our 10 year adventure in the open oceans on the ASX decades ago

The 3 letter codes may have changed over the ages but the hard lesson of diverging technical indicators should not be lost

This is particularly directed to the novice sea-cadet who for some unexplainable reason believes she’ll be right in the long term if onboard tall ships. It is also relevant to the seasoned veteran who after a magnificent season often forgets the principles of seamanship and lets his adrenalins rule.

Storm is that time all deep-sea yachtsmen must be prepared to face and sometimes without any warning. As we were sailing six tall ships all nearby in the ASX20 it made it possible to analyse the situation more closely afterwards.

The storm took place just south of New Zealand in an area not notorious for extremely fierce gales. However we were quite aware gales there may come suddenly and last for long periods. We weren’t concerned as each ship was toughly built and of heavy displacement. They were the pride of the ASX. Each and every broker in our network with research teams on many floors suggested the big three. BHP, NAB, and NCP and stressed a “diverse and balanced portfolio.”

Julius the only cadet on board asked

“What is the difference?”

Jack replied

“It’s a safety formula so that if any one or two get into trouble the other four will pull us through.” Henry quickly added

“Only if you have equal chips on all.”

We had opted for three industrials and three resources. Jack recommended BPC for its attractive price earning ratio and yield. Benji added WMC because he had fond memories. Henry added MIM as he considered her price a good value bet being the cheapest in the top 20. I abstained from joining the selection table as I saw my responsibility solely as the skipper and navigator.

We had already by now earned an excellent racing record and gained much ground, sailed through many spring gales and came through undamaged.

The NAB was far to the west and by chance the rest of our fleet were bunched together to the east.

On the 20th Dec 93 the chart of the NAB showed a bearish weather pattern and was first hit. There was no hint of a depression forming.

Yet with in 2 weeks the storm was establishing itself amongst the ships.

At midnight the storm caught us.

As the barometer plummeted (the white indicator, refer any chart later), violent wind gusts struck the yacht. All the sails were lowered and the boat put in the trough of the sea while we watched for any change. After one day the barometer had checked its fall and the wind’s mean easterly direction was unaltered. The torrential rainfall and screeching gusts all suggested we might be in the path of a revolving storm, or hurricane. The normal instructions for avoiding such storms could no longer be carried out, as the wind was too violent for any canvas to withstand.

The situation as it appeared at 1.00 am. in the middle watch was the very one we had studied most carefully. Not because it seemed likely, but because it was the worst possible position we could imagine for a sailing ship in the open sea.

I assessed that the loss of the tall mast was probable. In this lonely part of the ocean, 500 miles from America and with no engine, survival needed the preservation of all food and water. Nothing could be discarded to lighten the ship. I assessed that crew fatigue would be a danger should a breaking wave smash over the deck or cabin. Finally came the danger of crew being washed overboard. This seemed the greatest hazard of all.

It was clearly best to direct the end of the boat on to the sea to reduce the chance of a wave breaking over her. With such a strong crew I felt a helmsman could always be kept on deck. Even without sails the wind on the bare mast was driving us through the water at near maximum speed.

The night was black. My outlasting impression was noise. The shriek of the wind in the riggings, the din of the waves all blending into one devilish clamour and the pelting rain hammered against one’s head.

Moving around was not easy in these conditions. A novice helmsman could easily be caught off guard while shifting into position. Suddenly, a sea came pounding over the deck, filled the cockpit and slammed against the cabin. The ship was battened down so little water went below. Until one had been on deck for some time it was hard to believe that each succeeding wave would not wash over. If the helmsman could meet each wave squarely with the stern she would rise quietly with the sea and nothing but spray would come aboard.

The problem became chiefly a psychological one. As we were all quite experienced helmsmen by this stage no exceptional difficulty was found in steering the stern into the seas even in the dark. But it was decidedly frightening to hear the furious snarl of a wave breaking astern above the continuous roar of wind, rain, spray and waves hurling themselves at the boat.

I prayed earnestly for the dawn and went down below to look at the barometer. It was still falling steadily. There was a slight easing of the wind but it was still blowing a full gale. As man is a creature of daylight I felt that if we could just survive the night unharmed all will be well. However when dawn should have broken the angry darkness held its own.

Slowly the light seeped through the rain and spray. The dawn was much more frightening than the night. The sight of those huge waves building up astern was devastating. The surface took on a dull dirty and frothy white washing machine character. In the driving spray and rain one could scarcely see beyond the next crest even when on top of a wave.

I had been up all night and the sheer horror of looking at the seas I went below to check all the charts instruments, ate a block of chocolate and write up the log.

If on deck had felt overwhelmingly hostile, the cabin felt like a prison cell. The worst impression was one of utter helplessness. There nothing I could do except trust my instruments.

A spurt of water shot through the tiny peephole left for the helmsman to communicate with those below. I looked out and saw Jack signal me to come up. Conversation was impossible on deck but it was obvious he just wanted some support. He too was frightened by the sight and noise of the seas. Curiously, I found his anxiety reassuring. It did not seem to matter being afraid if a man of his calibre was feeling the same. In any case it felt better to be lending support to another. Strengthened in this way one could think and look around more objectively.

At 5.45 am. on the 25 May, the wind fell dead.

The sudden change was staggering. We had run into a patch of blue sky, colour sparkled, the rain dried up and the spray ceased to drive. On deck our voices were freed. Words no longer vanished in the storm.

“Look at that mountain of sea sir” Jack shouted, forgetting that his voice had not to compete with the elements,

‘It’s breaking in all directions at the top.”

The sea was hopelessly confused. Pinnacles of water would surge up without any form or rhythm. It seemed Mother Nature had developed a taste for modern art. One longed for some wind to steady her but dreaded the return of its overwhelming power. The boats motion was chaotic in the heavy air. Yet Henry and Ben below had somehow wedged and lashed themselves into their bunks. It takes a seaman to rest in such conditions. Every moment they could lie down strengthened our defence.

“I suppose we’re all right, sir,” said Jack doubtfully, “it really scared me to look at those huge curlers astern.”

“Yes, we’re all right,” I replied without much enthusiasm,

“But the real thing is what happens next.”

‘What does happen next, sir?”

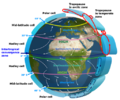

‘We seem to be in the eye of a storm, Jack. The strongest wind comes after the calm.”

“I bet no one else has looked into the eye of storm of this size.

“What are we going to do now, sir?”

“Can she stand any more of this ****?”

“She’s stood it so far, Jack. We’ve done all we can. We’re all well trained and ready. There’s nothing left but to pray.” The urge to prey was deep and we were both silent for a minute.

“We’ll pull her through, sir.” warm hearted, loyal Jack said. No finer man could exist to share the pressure. At last there was colour and blue sky, but the mental relief that had come when the wind no longer blew, fizzled out like a spent rocket.

All around swirling, angry, black curtain walls of sea hemmed us in. Seven minutes of a pregnant pause seemed ages.

Savagely the wind pounced again.

It was still from the east. I struggled to check the course from my second compass. (Daily charts explained later) I was surprised to discover they both did not point in a different direction. We were still heading south with the wind astern. I thought of St. Jude and the hope of the hopeless as we sped further from land.

The clock clung to every minute, but at last an hour had passed. The instruments were pumping up and down vigorously as we dived and soared. My obsession with safety was instinctive. My passion for life, insatiable. The hope for some rising indicators never came. At times their fall was checked and then slowly fell again. This was a bitter disappointment. Although I thought the skipper should constantly be on the alert there was nothing I could do about anything and went below to write up the log.

Perhaps the depression is still deepening?

Bon Voyage and Gods' speed

Captain Chaza