- Joined

- 13 February 2006

- Posts

- 5,272

- Reactions

- 12,138

Agricultural impact:

Murphy’s Law in the farm belt. This morning, Tyson Foods, Inc. announced the closing of its Waterloo, Iowa pork plant (the company’s largest) until further notice. Results of the planned testing of its 2,800-strong workforce will determine the timing of the plant's reopening.

That’s the third major pork-related closure in the past two weeks, after fellow meat giants JBS S.A. and Smithfield Foods, Inc. shuttered large facilities in Minnesota and South Dakota, respectively. In total, the three closed plants represent roughly 15% of domestic capacity. “Most of the trade believes these plants will be up and running by the first week in May,” Rich Nelson, chief strategist at Allendale, Inc., told Bloomberg. “The concern is that they are not.”

As plant closures roil supply, the evaporation of demand from restaurants and hotels further complicates life for the farm belt. As the Financial Times notes today, repurposing foodstuffs meant for commercial consumption to grocery stores is a tall order due to sometimes drastically different specifications for each category. Instead, farmers across the country have resorted to destroying their crops, in an echo of the early 1930s.

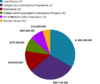

“We’re definitely taking on water really fast right now,” Jen Sorenson, incoming president of the National Pork Producers Council, told the FT. “The loss of packing capacity [from shuttered plants] is terrifying to producers because there is no place to take market animals.” According to data compiled by Axios, the beef, pork and dairy industries anticipate a combined $21.6 billion in losses owing to pandemic-related disruptions, outstripping the $16 billion in direct federal aid promised by the U.S. Department of Agriculture last week.

Things were far from hunky dory prior to the pandemic, as domestic farm debt hit a record high $416 billion in 2019, compared to $88 billion in farm income (of which roughly 40% came from government assistance). Distress among farmers began to creep higher last year, with the 30-day past due rate of agricultural loans reaching 2.06% in the fourth quarter according to the Federal Reserve, the highest since 2011 and more than double that seen at the end of 2015. In the 12 months through September, 580 farms declared Chapter 12 bankruptcy according to the American Farm Bureau Federation, up 24% from the prior year and a seven-year high.

Meanwhile, corn prices are under a two-fronted assault, as sharply curtailed gasoline demand reduces the need for corn-based ethanol, while lower pork prices and reduced pig supplies further upset the supply vs. demand equation. An anonymity-seeking investor walks Grant’s through the grim math for pork farmers:

Across most of last year, hog producers were able to generate a profit of roughly $40 per pig. As of today, the same producer would experience a $30 per pig loss, equating to a $22 million loss for 750,000 heads of livestock. The only way to survive is to execute the piglets as fast as possible – take to market about 20% of your breeding stock – and place on reduced rations the remaining sows.

The unhappy conclusion from our correspondent: “It is a blood bath out there in the real world.”

jog on

duc

Murphy’s Law in the farm belt. This morning, Tyson Foods, Inc. announced the closing of its Waterloo, Iowa pork plant (the company’s largest) until further notice. Results of the planned testing of its 2,800-strong workforce will determine the timing of the plant's reopening.

That’s the third major pork-related closure in the past two weeks, after fellow meat giants JBS S.A. and Smithfield Foods, Inc. shuttered large facilities in Minnesota and South Dakota, respectively. In total, the three closed plants represent roughly 15% of domestic capacity. “Most of the trade believes these plants will be up and running by the first week in May,” Rich Nelson, chief strategist at Allendale, Inc., told Bloomberg. “The concern is that they are not.”

As plant closures roil supply, the evaporation of demand from restaurants and hotels further complicates life for the farm belt. As the Financial Times notes today, repurposing foodstuffs meant for commercial consumption to grocery stores is a tall order due to sometimes drastically different specifications for each category. Instead, farmers across the country have resorted to destroying their crops, in an echo of the early 1930s.

“We’re definitely taking on water really fast right now,” Jen Sorenson, incoming president of the National Pork Producers Council, told the FT. “The loss of packing capacity [from shuttered plants] is terrifying to producers because there is no place to take market animals.” According to data compiled by Axios, the beef, pork and dairy industries anticipate a combined $21.6 billion in losses owing to pandemic-related disruptions, outstripping the $16 billion in direct federal aid promised by the U.S. Department of Agriculture last week.

Things were far from hunky dory prior to the pandemic, as domestic farm debt hit a record high $416 billion in 2019, compared to $88 billion in farm income (of which roughly 40% came from government assistance). Distress among farmers began to creep higher last year, with the 30-day past due rate of agricultural loans reaching 2.06% in the fourth quarter according to the Federal Reserve, the highest since 2011 and more than double that seen at the end of 2015. In the 12 months through September, 580 farms declared Chapter 12 bankruptcy according to the American Farm Bureau Federation, up 24% from the prior year and a seven-year high.

Meanwhile, corn prices are under a two-fronted assault, as sharply curtailed gasoline demand reduces the need for corn-based ethanol, while lower pork prices and reduced pig supplies further upset the supply vs. demand equation. An anonymity-seeking investor walks Grant’s through the grim math for pork farmers:

Across most of last year, hog producers were able to generate a profit of roughly $40 per pig. As of today, the same producer would experience a $30 per pig loss, equating to a $22 million loss for 750,000 heads of livestock. The only way to survive is to execute the piglets as fast as possible – take to market about 20% of your breeding stock – and place on reduced rations the remaining sows.

The unhappy conclusion from our correspondent: “It is a blood bath out there in the real world.”

jog on

duc