- Joined

- 13 February 2006

- Posts

- 5,493

- Reactions

- 13,009

Part 5

are responsible for adequately managing their risk exposure, but there may be a case for broader risk assessment in the future.

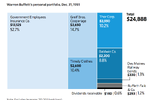

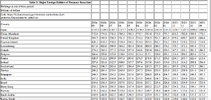

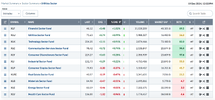

View attachment 189446

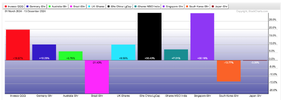

Meh week.

Chips:

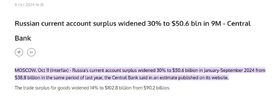

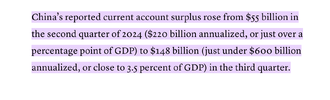

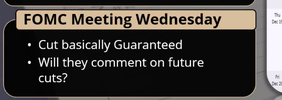

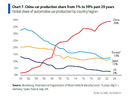

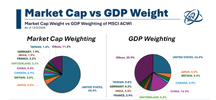

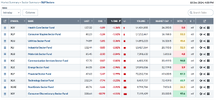

View attachment 189448View attachment 189447

On Luck:

Maybe a better way to frame luck is by asking: what isn’t repeatable?

Lucky implies random events you could not see coming. What isn’t repeatable is different. Did Jeff Bezos get lucky creating Amazon? Not in the same way a lottery winner is lucky, of course. He was visionary and ambitious and savvy to a degree you only see a few times per century.

But could he, starting today, without any money or name recognition, create a new multi-trillion dollar business from scratch?

Maybe, but probably not. There are so many things that helped Amazon become what it is that can’t be replicated – growth of the internet, market conditions, old competitors, politics, regulations, etc. Bezos is enormously skilled in a way that is not luck. But a lot of what he did was not repeatable. Those points are not contradictory.

It’s so important to know the difference between the two when attempting to learn from someone. You want to try to emulate skills that are repeatable. Attempting to copy the parts of someone’s success that aren’t repeatable is equivalent to a 56-year-old dressing like a teenager and expecting to be cool.

There’s a law in evolution called Dollo’s Law of Irreversibility that says once a species loses a trait, it will never gain that trait back because the path that gave it the trait in the first place was so complicated that it can’t be replicated. Say an animal has horns, and then it evolves to lose its horns. The odds that it will ever evolve to regain its horns are nil, because the path that originally gave it horns was so complex – millions of years of selection under specific environmental and competitive conditions that won’t repeat in the future. You can’t call evolutionary traits luck – they came about because of very specific forces. You just can’t ever rely on those forces repeating themselves exactly as they did in the past.

A lot of things work like that.

In business and investing, you want to learn the big lessons about why things behave the way they do without assuming the past is a direct guide to the future, because it’s not – most of the details are not repeatable. History is the study of change, ironically used as a map of the future.

Jason Zweig of the Wall Street Journal once talked about what happens when you try to learn a very specific, non-repeatable lesson when a broader, very repeatable lesson is what you needed to pay attention to:

You can learn a lot from Warren Buffett’s patience. But you can’t replicate the market environment he had in the 1950s, so be careful copying the specific strategies he used back then.

You can learn so much from John D. Rockefeller about the importance of controlling distribution. But you cannot replicate the 20th century legal system that allowed him to destroy competitors, so don’t get carried away there.

Elon Musk can teach you a lot about risk-taking and branding, but much less about competing in the auto business.

Jeff Bezos can teach you so much about management and long-term thinking, but much less about e-commerce and cloud computing.

The way to get luckier is to find what’s repeatable.

On investing:

I entered the workforce in 2005.

That means I’ve been working in the investment business for 20 years now.

The longer I’m in the money management business the more there is to learn but these are some of the things I’ve learned thus far:

1. Experiences shape your perception of risk. Your ability and need to take risk should be based on your stage in life, time horizon, financial circumstances and goals.

But your desire to take risk often trumps all that, depending on your life experiences. If you worked at Enron or Lehman Brothers or AIG or invested with Madoff, your appetite for risk will be forever altered.

And that’s OK as long as you plan accordingly.

2. Intelligence doesn’t guarantee investment success. Warren Buffett once wrote, “Investing is not a game where the guy with the 160 IQ beats the guy with the 130 IQ. Once you have ordinary intelligence, what you need is the temperament to control the urges that get other people into trouble in investing.”

I’ve met so many highly educated individuals who are terrible investors. They can’t control their emotions because their academic pedigree makes them overconfident in their abilities.

Emotional intelligence is the true sign of investment smarts.

3. No one lives life in the long-term. Long-term returns are the only ones that matter but you have to survive a series of short-terms to get there.

The good strategy you can stick with in those short-terms is preferable to the perfect strategy you can’t stick with.

4. The only client question that matters is: “Am I going to be OK?” Each situation is unique in that everyone has their own set of fears and desires.

The answer everyone is looking for is the same, though: Just tell me I’m going to be OK.

5. It’s never been easier or harder to set-it-and-forget-it. Investors have never had it better in terms of the ability to automate investments, contributions, allocations, rebalancing and dividend reinvestment.

But there has never been more temptation to tinker with your set-it-and-forget-it portfolio because of all the new investment products, funds, zero-commission trading platforms, and trading opportunities.

Every day it becomes harder and harder to avoid the new forbidden fruit.

6. Rich people hate paying taxes more than they like making more money. I’m only half kidding but the more money people have the more they look for ways to avoid paying Uncle Sam.

7. Getting rich overnight is a curse, not a blessing. I’m convinced that the people who build wealth slowly over the course of their career are far better equipped to handle money than those who come into it easily.

It means more to those who acquired wealth through patience and discipline.

8. Investing is hard. Ironically, coming to this realization can make it a little easier.

9. The biggest risks are always the same…yet different. The next risk is rarely the same as the last risk because every market environment is different.

On the other hand, the biggest mistakes investors make are often the same — timing the market, recency bias, being fearful when others are fearful and greedy when others are greedy and investing in the latest fads.

It’s always a different market but human nature is the constant.

10. The market doesn’t care how clever you are. There is no alpha for the degree of difficulty when investing.

Trying harder doesn’t guarantee more profits.

11. A product is not a portfolio and a portfolio is not a plan. The longer I do this, the more I realize that personal finance and financial planning are prerequisites for successful investing.

12. Overthinking can be just as debilitating as not thinking at all. Investing involves irreducible uncertainty about the future.

You have to become comfortable making investment decisions with imperfect information.

13. Career risk explains most irrational decisions in the investment business. There is a lot of nonsense that goes on in the investment business. Most of it can be explained by incentives.

14. There is no such thing as a perfect portfolio. The best portfolio is the one you can stick with come hell or high water, not the one that’s the most optimized for silly formulas or spreadsheets.

15. Our emotions are rigged, not the stock market. The stock market is one of the last respectable institutions. It’s not rigged against you or anyone else.

The Illuminati is not out to get you but your emotions just might be if you don’t know how to control them.

16. Experience is not the same as expertise. Just because you’ve been doing something for a long time doesn’t mean you’re an expert.

I know plenty of experienced investors who are constantly fighting the last war to their own detriment.

How many people who “called” the 2008 crash completely missed the ensuing bull market? All of them?

How many investment legends turn into permabears the older they get becasue they fail to recognize how markets have changed over time?

Loads of investment professionals who have been in the business for many years make the same mistakes over and over again.

17. Being right all the time is overrated. Making money is more important than being right in the market.

Predictions are more about ego than making money.

18. There is a big difference between rich and wealthy. Lots of rich people are miserable. These people are not wealthy, regardless of how much money they have.

There are plenty of people who wouldn’t be considered rich based on the size of their net worth who are wealthy beyond imagination because of their family, friends and general contentment with what they have.

19. Optimism should be your default. It saddens me to see an increasing number of cynical and pessimistic people every year.

I understand the world can be an unforgiving place and things will never be perfect but investing is a game where the optimists win.

20. Less is more. I’ve changed my mind on many investment-related topics over the years. But you will never convince me that complex is better than simple.

From Josh Brown:

I’m a former stockbroker with no formal education in economics or econometrics (the latter word, I couldn’t tell you what it means with a dictionary in my hand). I don’t know anything. I started in this business cold-calling Dun & Bradstreet index cards with the names and phone numbers of business owners. I’m an alumni of the speculative fever swamps of Stockbrokerland in Syosset, Long Island. No pedigree. Classically trained with a plastic black telephone, a headset and an Acer monitor running Quotron.

But, like most of you, I have my own two eyes and two ears to try to understand what’s going on. These have been valuable if we’ve learned how to use them.

Pragmatism and lived experience are significantly more helpful these days than anything else. If you spend most of your time around people who are in the top half of the wealth distribution, you’re not making recession calls. There’s simply no sign of one and there hasn’t been since the start of 2023.

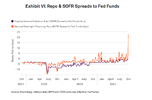

This is because one of the most interesting byproducts of the historic rate-hiking cycle the Federal Reserve embarked upon - and the subsequent “high for longer” period - has produced an unexpected result: Easy money. Never before in the last fifteen years have so many people been able to earn so much - virtually risk-free - in their bank and brokerage accounts. We’re talking about trillions of dollars in income and it keeps on coming. Combine this with record high stock prices and a boom in AI-related IT spending, plus pandemic-era stimulus programs kicking in and you get to where we are in 2024.

Anyone who wants a job can have a job. Wages are still rising in most industries. Home prices are holding. People are still shopping.

In 2022, CFOs at large corporations were certain that the confluence of inflationary pressures and the normal ebbs and flows of the economic cycle would bring about recession. According to the Duke University survey, they were nearly unanimous in this mindset. They prepared for it. Earnings growth went negative for multiple quarters as a result. And then, something totally outside of the formulas of the formally trained economists took place - high rates of income prolonged the expansion.

It wasn’t supposed to happen that way.

The overnight rate on money, it turns out, wasn’t as important as it had historically been. The inverted yield curve didn’t cause the cessation in lending it was supposed to have. Blame it on the fortress balance sheets of the nation’s largest banks, even as the midsized banks were stumbling last spring. Blame it on the renaissance in private credit, with capital on offer to any enterprise that spoke up to ask for it. Blame it on buoyant stock prices and the ocean of unspent cash at private equity funds just waiting to pounce on any and every opportunity. There are a lot of factors at play that simply were not in the models.

I have been speaking emphatically about the preeminence of the wealth effect for fifteen years. The stock market drives investment decisions at the largest companies and it fuels consumer spending, which is 70% of the economy. Even 401(k) balances, which cannot be touched, have an effect on the way people feel and therefore drive household decision-making and budgeting.

There is a growing recognition that record high interest income is working counter to the Fed's goals of slowing down demand. Very intelligent people were ridiculing this idea last year. Now it’s becoming a mainstream point of view. Rick Rieder is the head of fixed income at BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager. If anyone is in a position to see what’s going on, surely it would be Rick. Rick confirms what I’ve been saying.

Randall Forsyth used his column in Barron’s this weekend to comment on the subject, citing the latest government data:

American households’ net worth jumped by $5.1 trillion, or 3.3%, in the first quarter, according to the latest data released by the Fed on Friday.

More than half of that gain was accounted for by their increase in equities and mutual fund holdings.

And they earned an annualized $3.7 trillion from interest and dividends in the first quarter, up roughly $770 billion from four years earlier

My father-in-law Harry, a CPA, explained to me that older wealthy people in the early 1980’s absolutely loved high interest rates. Their bank accounts bulged with interest, igniting their ability to live large and spend. Brokers at that time were selling CDs and bonds with obscenely high rates of interest to an insatiable audience of well-to-do buyers.

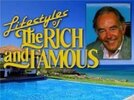

It’s not an accident that the television show ‘Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous” was conceived during this time in America coinciding with the highest interest rates on record: The federal funds rate was 20% (!) in 1980, staying in the mid-to-high teens throughout the period ending in 1982. Wealthy old guys without mortgages or, frankly, a care in the world saw their money compound at incredible rates. In 1984, Robin Leach hit the airwaves for the first time showing TV audiences the unparalleled wealth and success that had been attained by this select group of people. The supercilious tone of his narration and his distinctively British accent became a soundtrack of sorts to the earliest stages of the secular bull market that would run for another 16 years.

Remember this?

My post at the top of a wealth management firm has given me a bird’s eye view of what people are actually doing and thinking and saying in real life, as opposed to what they ought to be doing, thinking and saying according to the past. None of what I am seeing or hearing aligns at all with what most would have expected this far into a hiking cycle.

Outside of commercial real estate, the behavior of investors and consumers simply has not conformed to the expectations that would have been considered reasonable as recently as a few years ago.

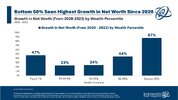

I would point out that it’s not just the wealthiest who’ve benefited from the current situation.

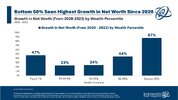

Ben Carlson’s post, “The Bottom 50%” makes it clear that net worths have been expanding for all cohorts…

Of course, the bottom 50% of households are seeing larger gains mostly due to the effect of it coming off a smaller base, but still.

Here’s the cash sitting in banks belonging to the bottom 50%:

That’s $280 billion, despite what you’ve heard about people “blowing through their pandemic cushion.” Now, of course, not all of this money is earning a high interest rate because the largest banks have gotten away with not passing it along. But a lot of it is earning higher rates. This is not to say that’s negating the poor sentiment around higher costs in the economy - Americans despise inflation, after all. But I would say that these higher rates on savings are offsetting the effect of high prices practically. Just enough to keep the expansion going. Even if they keep telling the surveyors that they are miserable.

I want to make it clear that what I’m describing here is simply an explanation for what has already transpired. I do not believe this is a permanent condition. As unexpected as the recent environment has been, we should not extrapolate these ideas further and fall into the trap of pondering the end of all economic cycles. The cycle will resume. The worm will turn. It’s only a matter of when, not if. But cycles can take a long time to play out. Especially when they’re being driven by unforeseen forces like this once-in-a-lifetime boom in investment income.

That’s all from me today. Until next time - Champagne Wishes and Caviar Dreams!

jog on

duc

are responsible for adequately managing their risk exposure, but there may be a case for broader risk assessment in the future.

View attachment 189446

Meh week.

Chips:

View attachment 189448View attachment 189447

On Luck:

Maybe a better way to frame luck is by asking: what isn’t repeatable?

Lucky implies random events you could not see coming. What isn’t repeatable is different. Did Jeff Bezos get lucky creating Amazon? Not in the same way a lottery winner is lucky, of course. He was visionary and ambitious and savvy to a degree you only see a few times per century.

But could he, starting today, without any money or name recognition, create a new multi-trillion dollar business from scratch?

Maybe, but probably not. There are so many things that helped Amazon become what it is that can’t be replicated – growth of the internet, market conditions, old competitors, politics, regulations, etc. Bezos is enormously skilled in a way that is not luck. But a lot of what he did was not repeatable. Those points are not contradictory.

It’s so important to know the difference between the two when attempting to learn from someone. You want to try to emulate skills that are repeatable. Attempting to copy the parts of someone’s success that aren’t repeatable is equivalent to a 56-year-old dressing like a teenager and expecting to be cool.

There’s a law in evolution called Dollo’s Law of Irreversibility that says once a species loses a trait, it will never gain that trait back because the path that gave it the trait in the first place was so complicated that it can’t be replicated. Say an animal has horns, and then it evolves to lose its horns. The odds that it will ever evolve to regain its horns are nil, because the path that originally gave it horns was so complex – millions of years of selection under specific environmental and competitive conditions that won’t repeat in the future. You can’t call evolutionary traits luck – they came about because of very specific forces. You just can’t ever rely on those forces repeating themselves exactly as they did in the past.

A lot of things work like that.

In business and investing, you want to learn the big lessons about why things behave the way they do without assuming the past is a direct guide to the future, because it’s not – most of the details are not repeatable. History is the study of change, ironically used as a map of the future.

Jason Zweig of the Wall Street Journal once talked about what happens when you try to learn a very specific, non-repeatable lesson when a broader, very repeatable lesson is what you needed to pay attention to:

The great thing when you ask, “is this repeatable?” is that you start to focus on things that you and I – ordinary lay people – have a chance of repeating ourselves.[After the dot-com crash], the lesson people learned from that was not, “I should never speculate on overvalued financial assets.” The lesson they learned was, “I should never speculate on internet stocks.” And so the same people who lost 90% or more of their money day-trading internet stocks ended up flipping homes in the mid 2000s, and getting wiped out doing that. It’s dangerous to learn narrow lessons.

You can learn a lot from Warren Buffett’s patience. But you can’t replicate the market environment he had in the 1950s, so be careful copying the specific strategies he used back then.

You can learn so much from John D. Rockefeller about the importance of controlling distribution. But you cannot replicate the 20th century legal system that allowed him to destroy competitors, so don’t get carried away there.

Elon Musk can teach you a lot about risk-taking and branding, but much less about competing in the auto business.

Jeff Bezos can teach you so much about management and long-term thinking, but much less about e-commerce and cloud computing.

The way to get luckier is to find what’s repeatable.

On investing:

I entered the workforce in 2005.

That means I’ve been working in the investment business for 20 years now.

The longer I’m in the money management business the more there is to learn but these are some of the things I’ve learned thus far:

1. Experiences shape your perception of risk. Your ability and need to take risk should be based on your stage in life, time horizon, financial circumstances and goals.

But your desire to take risk often trumps all that, depending on your life experiences. If you worked at Enron or Lehman Brothers or AIG or invested with Madoff, your appetite for risk will be forever altered.

And that’s OK as long as you plan accordingly.

2. Intelligence doesn’t guarantee investment success. Warren Buffett once wrote, “Investing is not a game where the guy with the 160 IQ beats the guy with the 130 IQ. Once you have ordinary intelligence, what you need is the temperament to control the urges that get other people into trouble in investing.”

I’ve met so many highly educated individuals who are terrible investors. They can’t control their emotions because their academic pedigree makes them overconfident in their abilities.

Emotional intelligence is the true sign of investment smarts.

3. No one lives life in the long-term. Long-term returns are the only ones that matter but you have to survive a series of short-terms to get there.

The good strategy you can stick with in those short-terms is preferable to the perfect strategy you can’t stick with.

4. The only client question that matters is: “Am I going to be OK?” Each situation is unique in that everyone has their own set of fears and desires.

The answer everyone is looking for is the same, though: Just tell me I’m going to be OK.

5. It’s never been easier or harder to set-it-and-forget-it. Investors have never had it better in terms of the ability to automate investments, contributions, allocations, rebalancing and dividend reinvestment.

But there has never been more temptation to tinker with your set-it-and-forget-it portfolio because of all the new investment products, funds, zero-commission trading platforms, and trading opportunities.

Every day it becomes harder and harder to avoid the new forbidden fruit.

6. Rich people hate paying taxes more than they like making more money. I’m only half kidding but the more money people have the more they look for ways to avoid paying Uncle Sam.

7. Getting rich overnight is a curse, not a blessing. I’m convinced that the people who build wealth slowly over the course of their career are far better equipped to handle money than those who come into it easily.

It means more to those who acquired wealth through patience and discipline.

8. Investing is hard. Ironically, coming to this realization can make it a little easier.

9. The biggest risks are always the same…yet different. The next risk is rarely the same as the last risk because every market environment is different.

On the other hand, the biggest mistakes investors make are often the same — timing the market, recency bias, being fearful when others are fearful and greedy when others are greedy and investing in the latest fads.

It’s always a different market but human nature is the constant.

10. The market doesn’t care how clever you are. There is no alpha for the degree of difficulty when investing.

Trying harder doesn’t guarantee more profits.

11. A product is not a portfolio and a portfolio is not a plan. The longer I do this, the more I realize that personal finance and financial planning are prerequisites for successful investing.

12. Overthinking can be just as debilitating as not thinking at all. Investing involves irreducible uncertainty about the future.

You have to become comfortable making investment decisions with imperfect information.

13. Career risk explains most irrational decisions in the investment business. There is a lot of nonsense that goes on in the investment business. Most of it can be explained by incentives.

14. There is no such thing as a perfect portfolio. The best portfolio is the one you can stick with come hell or high water, not the one that’s the most optimized for silly formulas or spreadsheets.

15. Our emotions are rigged, not the stock market. The stock market is one of the last respectable institutions. It’s not rigged against you or anyone else.

The Illuminati is not out to get you but your emotions just might be if you don’t know how to control them.

16. Experience is not the same as expertise. Just because you’ve been doing something for a long time doesn’t mean you’re an expert.

I know plenty of experienced investors who are constantly fighting the last war to their own detriment.

How many people who “called” the 2008 crash completely missed the ensuing bull market? All of them?

How many investment legends turn into permabears the older they get becasue they fail to recognize how markets have changed over time?

Loads of investment professionals who have been in the business for many years make the same mistakes over and over again.

17. Being right all the time is overrated. Making money is more important than being right in the market.

Predictions are more about ego than making money.

18. There is a big difference between rich and wealthy. Lots of rich people are miserable. These people are not wealthy, regardless of how much money they have.

There are plenty of people who wouldn’t be considered rich based on the size of their net worth who are wealthy beyond imagination because of their family, friends and general contentment with what they have.

19. Optimism should be your default. It saddens me to see an increasing number of cynical and pessimistic people every year.

I understand the world can be an unforgiving place and things will never be perfect but investing is a game where the optimists win.

20. Less is more. I’ve changed my mind on many investment-related topics over the years. But you will never convince me that complex is better than simple.

From Josh Brown:

I’m a former stockbroker with no formal education in economics or econometrics (the latter word, I couldn’t tell you what it means with a dictionary in my hand). I don’t know anything. I started in this business cold-calling Dun & Bradstreet index cards with the names and phone numbers of business owners. I’m an alumni of the speculative fever swamps of Stockbrokerland in Syosset, Long Island. No pedigree. Classically trained with a plastic black telephone, a headset and an Acer monitor running Quotron.

But, like most of you, I have my own two eyes and two ears to try to understand what’s going on. These have been valuable if we’ve learned how to use them.

Pragmatism and lived experience are significantly more helpful these days than anything else. If you spend most of your time around people who are in the top half of the wealth distribution, you’re not making recession calls. There’s simply no sign of one and there hasn’t been since the start of 2023.

This is because one of the most interesting byproducts of the historic rate-hiking cycle the Federal Reserve embarked upon - and the subsequent “high for longer” period - has produced an unexpected result: Easy money. Never before in the last fifteen years have so many people been able to earn so much - virtually risk-free - in their bank and brokerage accounts. We’re talking about trillions of dollars in income and it keeps on coming. Combine this with record high stock prices and a boom in AI-related IT spending, plus pandemic-era stimulus programs kicking in and you get to where we are in 2024.

Anyone who wants a job can have a job. Wages are still rising in most industries. Home prices are holding. People are still shopping.

In 2022, CFOs at large corporations were certain that the confluence of inflationary pressures and the normal ebbs and flows of the economic cycle would bring about recession. According to the Duke University survey, they were nearly unanimous in this mindset. They prepared for it. Earnings growth went negative for multiple quarters as a result. And then, something totally outside of the formulas of the formally trained economists took place - high rates of income prolonged the expansion.

It wasn’t supposed to happen that way.

The overnight rate on money, it turns out, wasn’t as important as it had historically been. The inverted yield curve didn’t cause the cessation in lending it was supposed to have. Blame it on the fortress balance sheets of the nation’s largest banks, even as the midsized banks were stumbling last spring. Blame it on the renaissance in private credit, with capital on offer to any enterprise that spoke up to ask for it. Blame it on buoyant stock prices and the ocean of unspent cash at private equity funds just waiting to pounce on any and every opportunity. There are a lot of factors at play that simply were not in the models.

I have been speaking emphatically about the preeminence of the wealth effect for fifteen years. The stock market drives investment decisions at the largest companies and it fuels consumer spending, which is 70% of the economy. Even 401(k) balances, which cannot be touched, have an effect on the way people feel and therefore drive household decision-making and budgeting.

There is a growing recognition that record high interest income is working counter to the Fed's goals of slowing down demand. Very intelligent people were ridiculing this idea last year. Now it’s becoming a mainstream point of view. Rick Rieder is the head of fixed income at BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager. If anyone is in a position to see what’s going on, surely it would be Rick. Rick confirms what I’ve been saying.

Randall Forsyth used his column in Barron’s this weekend to comment on the subject, citing the latest government data:

American households’ net worth jumped by $5.1 trillion, or 3.3%, in the first quarter, according to the latest data released by the Fed on Friday.

More than half of that gain was accounted for by their increase in equities and mutual fund holdings.

And they earned an annualized $3.7 trillion from interest and dividends in the first quarter, up roughly $770 billion from four years earlier

My father-in-law Harry, a CPA, explained to me that older wealthy people in the early 1980’s absolutely loved high interest rates. Their bank accounts bulged with interest, igniting their ability to live large and spend. Brokers at that time were selling CDs and bonds with obscenely high rates of interest to an insatiable audience of well-to-do buyers.

It’s not an accident that the television show ‘Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous” was conceived during this time in America coinciding with the highest interest rates on record: The federal funds rate was 20% (!) in 1980, staying in the mid-to-high teens throughout the period ending in 1982. Wealthy old guys without mortgages or, frankly, a care in the world saw their money compound at incredible rates. In 1984, Robin Leach hit the airwaves for the first time showing TV audiences the unparalleled wealth and success that had been attained by this select group of people. The supercilious tone of his narration and his distinctively British accent became a soundtrack of sorts to the earliest stages of the secular bull market that would run for another 16 years.

Remember this?

My post at the top of a wealth management firm has given me a bird’s eye view of what people are actually doing and thinking and saying in real life, as opposed to what they ought to be doing, thinking and saying according to the past. None of what I am seeing or hearing aligns at all with what most would have expected this far into a hiking cycle.

Outside of commercial real estate, the behavior of investors and consumers simply has not conformed to the expectations that would have been considered reasonable as recently as a few years ago.

I would point out that it’s not just the wealthiest who’ve benefited from the current situation.

Ben Carlson’s post, “The Bottom 50%” makes it clear that net worths have been expanding for all cohorts…

Of course, the bottom 50% of households are seeing larger gains mostly due to the effect of it coming off a smaller base, but still.

Here’s the cash sitting in banks belonging to the bottom 50%:

That’s $280 billion, despite what you’ve heard about people “blowing through their pandemic cushion.” Now, of course, not all of this money is earning a high interest rate because the largest banks have gotten away with not passing it along. But a lot of it is earning higher rates. This is not to say that’s negating the poor sentiment around higher costs in the economy - Americans despise inflation, after all. But I would say that these higher rates on savings are offsetting the effect of high prices practically. Just enough to keep the expansion going. Even if they keep telling the surveyors that they are miserable.

I want to make it clear that what I’m describing here is simply an explanation for what has already transpired. I do not believe this is a permanent condition. As unexpected as the recent environment has been, we should not extrapolate these ideas further and fall into the trap of pondering the end of all economic cycles. The cycle will resume. The worm will turn. It’s only a matter of when, not if. But cycles can take a long time to play out. Especially when they’re being driven by unforeseen forces like this once-in-a-lifetime boom in investment income.

That’s all from me today. Until next time - Champagne Wishes and Caviar Dreams!

| The markets might be changing rapidly around us, but the billionaire beefs are not. More than 20 years after their Hallwood Realty deal went all pear-shaped, and long after they played chicken over Herbalife, it turns out Bill Ackman and Carl Icahn are still feuding. Ackman, who's currently winning the Robin Hood Foundation's charity stock-picking contest, confirmed on X today that his short idea for the competition is none other than Icahn's own IEP. While the HLF short was a tough one for Bill, the IEP trade looks much better - Icahn's namesake stock is down 19% in just the last month. Your move, Carl. |

| Stock indexes today are mixed, with the Nasdaq-100 posting a new all-time high and the Dow Jones Industrial Average posting a 3-week low. Broadcom is up more than +20% to lead the Nasdaq after predicting sales of its AI products will surge +65% in the fiscal first quarter; however, the S&P 500 gave up an early advance and turned lower after the 10-year T-note yield rose to a 2-1/2 week high. |

jog on

duc