- Joined

- 20 May 2008

- Posts

- 1,158

- Reactions

- 8

Now I know charities have expenditures, but $250K for a CEO? Kind of defeats the purpose of being a "charity" IMO...

"How society's helping hands may be dipping into your pockets"

December 27, 2008

It's hard to know exactly where your donations go, writes Brian Robins.

CHRISTMAS marks the giving time of year and with charities and other not-for-profit organisations receiving upwards of $7 billion annually, the lack of scrutiny is striking. For part of the economy that employs almost 900,000 people and enjoys annual income of $75 billion, with a healthy portion of this received from Federal, State and local governments, reform is long overdue.

The lack of uniform reporting standards means that it is often difficult to know whether your donations, or funds given by the Government, for example, are lining the pockets of managers and employees or not. You may think every dollar you give goes to that poor family in need, or that child in Africa, or whatever the cause that prompted you to dig deep, but rarely is this the case. Once management and promotional expenses are taken into account, often precious little makes its way to the intended beneficiary.

And that is only the start. A host of other governance issues needs to be addressed by an industry that assiduously mines your goodwill to its own ends.

The Senate recently concluded an inquiry into charitable and not-for-profit groups which made a host of commonsense recommendations - from a national reporting standard to having all fund-raising undertaken under national legislation, taking these powers from the states.

It also wants a uniform standard of accounts, which would make it easier for donors to understand just how "efficient" each organisation is in channelling donations to their intended recipient, for example, and managing their own costs.

The 2008 annual Givewell Survey of Australian Charities noted a further improvement in the number of registered charities disclosing fund-raising costs, which now stands at 59 per cent, up from 56 per cent a year earlier. That still means more than one in three charities hide this vital figure. Givewell argued the improvement in recent years reflects heightened criticism and scrutiny of charities following the surge in donations in the wake of the 2004 tsunami.

Of those charities that disclose fund-raising costs, the survey found the level was steady at 19 per cent of funds raised. But the different ways this figure is arrived at by charities casts doubt on its accuracy. "Donor confidence will only continue if positive trends in levels of disclosure persist. In the frugal times that lie ahead, convincing donors that their money is being well spent will be a key factor," Givewell said.

With the economy facing a slowdown, this will see donations cut at a time when many charities will be faced with rising demand for their services, forcing them to be more cautious in managing their funds in hand.

These pressures also come as many charities have lost heavily on investments thanks to the downturn in financial markets.

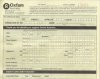

Go to Oxfam Australia's annual report, for example, and you find that it has lost $4 million in the sharemarket. Putting money into shares may not be what you expect of a charitable group entrusted with your donations. Oxfam Australia still has millions of dollars tied up in local and overseas sharemarkets. It was not alone, with the Cancer Council losing $7 million, to take just one other example.

Other charities, such as the Salvation Army, also have sizeable investment portfolios. However, the Salvos gives donors scant information about any aspect of its operations, similar to other large, long-standing charities such as the St Vincent de Paul Society, even though both raise tens of millions of dollars from both the public and the Government.

As with any business, top managers of charities and not-for-profit groups are not averse to putting their hand out seeking ever higher salaries, with wage inflation increasingly evident. It is not uncommon to come across people in the sector earning well over $150,000 a year and, in some cases, more than $200,000. World Vision's Tim Costello, for example, receives more than $250,000 a year - four times average weekly earnings, and up 25 per cent over the past year - which probably puts him at the pinnacle of the salaries paid in the sector (although, to be fair, few other charities detail their top salaries).

In the US, philanthropists and entrepreneurs have proposed a rating system to help donors decide whether a charity is worth receiving their money. The "Social Investing Rating Tool" is to assess how not-for-profit groups spend their money and, perhaps more fundamentally, whether their work makes a difference.

With so many charities in Australia failing to reach even the first step of detailing how they use your money, the task confronting the sector here is much more fundamental.

"How society's helping hands may be dipping into your pockets"

December 27, 2008

It's hard to know exactly where your donations go, writes Brian Robins.

CHRISTMAS marks the giving time of year and with charities and other not-for-profit organisations receiving upwards of $7 billion annually, the lack of scrutiny is striking. For part of the economy that employs almost 900,000 people and enjoys annual income of $75 billion, with a healthy portion of this received from Federal, State and local governments, reform is long overdue.

The lack of uniform reporting standards means that it is often difficult to know whether your donations, or funds given by the Government, for example, are lining the pockets of managers and employees or not. You may think every dollar you give goes to that poor family in need, or that child in Africa, or whatever the cause that prompted you to dig deep, but rarely is this the case. Once management and promotional expenses are taken into account, often precious little makes its way to the intended beneficiary.

And that is only the start. A host of other governance issues needs to be addressed by an industry that assiduously mines your goodwill to its own ends.

The Senate recently concluded an inquiry into charitable and not-for-profit groups which made a host of commonsense recommendations - from a national reporting standard to having all fund-raising undertaken under national legislation, taking these powers from the states.

It also wants a uniform standard of accounts, which would make it easier for donors to understand just how "efficient" each organisation is in channelling donations to their intended recipient, for example, and managing their own costs.

The 2008 annual Givewell Survey of Australian Charities noted a further improvement in the number of registered charities disclosing fund-raising costs, which now stands at 59 per cent, up from 56 per cent a year earlier. That still means more than one in three charities hide this vital figure. Givewell argued the improvement in recent years reflects heightened criticism and scrutiny of charities following the surge in donations in the wake of the 2004 tsunami.

Of those charities that disclose fund-raising costs, the survey found the level was steady at 19 per cent of funds raised. But the different ways this figure is arrived at by charities casts doubt on its accuracy. "Donor confidence will only continue if positive trends in levels of disclosure persist. In the frugal times that lie ahead, convincing donors that their money is being well spent will be a key factor," Givewell said.

With the economy facing a slowdown, this will see donations cut at a time when many charities will be faced with rising demand for their services, forcing them to be more cautious in managing their funds in hand.

These pressures also come as many charities have lost heavily on investments thanks to the downturn in financial markets.

Go to Oxfam Australia's annual report, for example, and you find that it has lost $4 million in the sharemarket. Putting money into shares may not be what you expect of a charitable group entrusted with your donations. Oxfam Australia still has millions of dollars tied up in local and overseas sharemarkets. It was not alone, with the Cancer Council losing $7 million, to take just one other example.

Other charities, such as the Salvation Army, also have sizeable investment portfolios. However, the Salvos gives donors scant information about any aspect of its operations, similar to other large, long-standing charities such as the St Vincent de Paul Society, even though both raise tens of millions of dollars from both the public and the Government.

As with any business, top managers of charities and not-for-profit groups are not averse to putting their hand out seeking ever higher salaries, with wage inflation increasingly evident. It is not uncommon to come across people in the sector earning well over $150,000 a year and, in some cases, more than $200,000. World Vision's Tim Costello, for example, receives more than $250,000 a year - four times average weekly earnings, and up 25 per cent over the past year - which probably puts him at the pinnacle of the salaries paid in the sector (although, to be fair, few other charities detail their top salaries).

In the US, philanthropists and entrepreneurs have proposed a rating system to help donors decide whether a charity is worth receiving their money. The "Social Investing Rating Tool" is to assess how not-for-profit groups spend their money and, perhaps more fundamentally, whether their work makes a difference.

With so many charities in Australia failing to reach even the first step of detailing how they use your money, the task confronting the sector here is much more fundamental.