QE is printing [currency] money. It is not credit creation, which is a separate form of money creation.

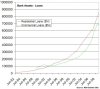

Simply observe M1

Yes but M1 is likely to increase in response to the "new money" being injected into the system via the QE, low interest rates (increased demand/supply of credit) etc. But it is not increasing because the Fed has physically printed the cash (or directly asked Treasury to) and handed it over to someone. Also, in the US, M1 includes both physical cash/notes in circulation and central bank deposits, so have to remember that when looking at M1 graphs etc.

As Macquack points out, notes in circulation only ever represents a small percentage of the amount of "money" in existence. Cash is "printed" as required based on what people demand (via withdrawals from banks, cash payrolls etc etc).

At the end of the day the point is moot anyway, regardless of the actual mechanism, the result in an increase in the amount of money that exists in that economic system. That creates the *potential* for inflation, both in the short term and the longer term, depending on what else is going on, how the economy reacts to the increased money supply etc etc. Clearly how much and what the risk is can be debated!

Cheers,

Beej