- Joined

- 18 November 2021

- Posts

- 76

- Reactions

- 103

Hello you nice and very intelligent people that make up this forum. I sincerely hope you are happy today.

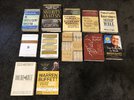

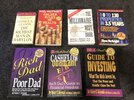

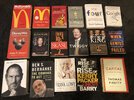

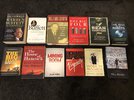

I have been a long term investor for a few years and find myself reading alot about what it takes to pick a quality stock and a checklist for what i should be looking for. I am constantly trying to learn more about investing and want to better my knowledge. I kindly wondered please what books you may have read regarding long term investing and how to have success hopefully finding a multi bagger stock and to perform well over the long term? Further any book that is highly recommended or classed as the most enlightening in the industry please?

I would appreciate it greatly for any advice you can give. Thank you very much and i hope you continue to do very well with your investing.

I have been a long term investor for a few years and find myself reading alot about what it takes to pick a quality stock and a checklist for what i should be looking for. I am constantly trying to learn more about investing and want to better my knowledge. I kindly wondered please what books you may have read regarding long term investing and how to have success hopefully finding a multi bagger stock and to perform well over the long term? Further any book that is highly recommended or classed as the most enlightening in the industry please?

I would appreciate it greatly for any advice you can give. Thank you very much and i hope you continue to do very well with your investing.