JohnDe

La dolce vita

- Joined

- 11 March 2020

- Posts

- 4,156

- Reactions

- 6,170

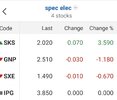

Looking at investment ideas and came across GE Vernova Inc

Scott Strazik, boss of GE Vernova, a power-equipment business that was spun out from the conglomerate last year, sees a “supercycle” in the making. Demand for everything from transformers and switchgears to high-voltage transmission cables is being turbocharged. The International Energy Agency (iea), an official forecaster, estimates that global investment in grid infrastructure reached nearly $400bn in 2024, up from a little over $300bn in 2020 and reversing a decline that began in 2017 on the back of slowing demand in China (see chart 2). The iea forecasts that spending will rise to around $600bn annually by 2030.

Goldman Sachs, a bank, estimates that India’s grid will require $100bn of investment between 2024 and 2032 as its economy grows.

Rystad, an energy consultancy, forecasts that annual grid investment in China will increase from around $100bn in 2024 to more than $150bn by 2030.

A new electricity supercycle is under way

Why spending on power infrastructure is surging around the world

The factory floor of Schneider Electric’s plant in Conselve, Italy, hums with urgency. Workers at the power-equipment company’s facility, which is in the midst of a major expansion, are busily assembling advanced cooling systems for the data centres underpinning the development of artificial intelligence (ai). “The key is the integration of grid to chip and chip to chiller,” says Pankaj Sharma, an executive at the company, referring to a new design it recently developed with Nvidia, an ai chip giant.

Over the past year Schneider’s market capitalisation has risen by over a third, to around $140bn. It is not the only maker of electrical gear that is booming (see chart 1). The market value of Hitachi, a Japanese conglomerate, has tripled since the start of 2022, thanks in part to the rapid expansion of its power-equipment division. After a difficult 2023, weighed down by troubles in its wind-turbine division, shares in Siemens Energy rose by 300% last year, outperforming even those of Nvidia, owing to fast-growing sales in the German firm’s grid-technology business. “Electricity is a key driver for us,” explains Christian Bruch, its chief executive.

Scott Strazik, boss of ge Vernova, a power-equipment business that was spun out from the conglomerate last year, sees a “supercycle” in the making. Demand for everything from transformers and switchgears to high-voltage transmission cables is being turbocharged. The International Energy Agency (iea), an official forecaster, estimates that global investment in grid infrastructure reached nearly $400bn in 2024, up from a little over $300bn in 2020 and reversing a decline that began in 2017 on the back of slowing demand in China (see chart 2). The iea forecasts that spending will rise to around $600bn annually by 2030. What is behind the surge?

The decarbonisation of electricity generation is one factor. Adding wind and solar power, often in remote locations, requires extending power lines and investing in hardware and software to help manage their intermittency. In Britain, the government’s ambition to achieve a net-zero grid by 2030 has prompted network operators to submit investment proposals amounting to nearly $100bn over five years. Even in America, where the incoming president is a climate-change denier, investment in renewable energy is expected to continue rising in the years ahead thanks to the plummeting cost of solar and wind power.

Electricity’s rising share of energy consumption is a second force propelling investment. The iea forecasts that demand for electricity, from both clean and dirty sources, will grow six times as fast as energy overall in the decade ahead, as it powers a growing share of cars, home-heating systems and industrial processes. California alone will need $50bn in electricity-distribution upgrades by 2035 to charge its electric vehicles (evs). Mr Strazik of ge Vernova reckons that this shift from “molecules to electrons” is just getting started.

The world’s total energy needs are also continuing to rise—a third force underpinning rising investment in electricity infrastructure. Economic growth, and rising use of air-conditioning, are pushing up demand in developing countries. Goldman Sachs, a bank, estimates that India’s grid will require $100bn of investment between 2024 and 2032 as its economy grows. Rystad, an energy consultancy, forecasts that annual grid investment in China will increase from around $100bn in 2024 to more than $150bn by 2030.

Spending by tech giants on ai is contributing to rising energy demand, too, flowing through to increased electricity consumption and investment. Some data centres gobble up as much energy as a nuclear-power plant generates, requiring network operators to upgrade transformers, power lines and control equipment. To accommodate the growth of data centres Tokyo Electric, Japan’s largest power utility, plans to spend more than $3bn by 2027 on its infrastructure. The boom in data centres has also caused spending by developers on cooling equipment and other ancillary electrical gear to rocket.

A final force behind the investment surge is grid fortification. Extreme weather events, from deadly storms to raging wild fires, are growing more common, causing over $100bn in damages worldwide in 2023. Only about half of that was covered by insurance. In December America’s Department of Energy provided a $15bn loan guarantee to pg&e, a Californian power utility hit hard by wildfires in recent years, to help it invest in making its grid more resilient. Across much of the rich world, electricity grids are old and creaking. In Europe the infrastructure is over 40 years old, on average. “Grid infrastructure was not built for resilience but for transmission,” says Mr Bruch of Siemens Energy.

As investment in grid infrastructure has soared, bottlenecks have emerged in the supply chain. Wood Mackenzie, another energy consultancy, estimates that a global shortage of transformers has led prices to rise by 60-80% since 2020, with waiting times tripling to five years or longer. That is spurring both capital spending and innovation among suppliers. Mr Bruch says his firm is investing record amounts to tackle an order backlog that now exceeds €120bn ($124bn). geVernova, whose backlog for electrical gear has reached $42bn, has said it will plough $9bn into capital expenditure and research and development by 2028. Hitachi’s energy business, which also has a hefty backlog, has spent $3bn on capital expenditure over the past three years and plans to spend another $6bn by 2027, including $1.5bn in transformers.

Expanding manufacturing capacity will leave these firms exposed if the electricity supercycle turns out to be no such thing. Growth in ev sales has already slowed in many rich countries. The ai boom could yet turn to bust. To reassure shareholders, Andreas Schierenbeck, boss of Hitachi’s energy business, says that his company has been getting big customers to reserve capacity with upfront payments, and is shifting from customised orders to framework contracts with standardised designs. All this makes future revenue more dependable and expanding production capacity less risky.

For now, spending on electricity infrastructure shows no sign of easing, as grid operators grapple with rising power consumption, a changing generation mix and ageing infrastructure. Those pressures will only increase, predicts Mr Bruch. “That is why we are bullish.”